About Christopher Stookey

Christopher Stookey, MD, is a practicing emergency physician, and he is passionate about medicine and health care. However, his other great interests are literature and writing, and he has steadily published a number of short stories and essays over the past ten years. His most recent essay, “First in My Class,” appears in the book BECOMING A DOCTOR (published by W. W. Norton & Co, March 2010); the essay describes Dr. Stookey’s wrenching involvement in a malpractice lawsuit when he was a new resident, fresh out of medical school. TERMINAL CARE, a medical mystery thriller, is his first novel. The book, set in San Francisco, explores the unsavory world of big-business pharmaceuticals as well as the sad and tragic world of the Alzheimer’s ward at a medical research hospital. Stookey’s other interests include jogging in the greenbelts near his home and surfing (he promises his next novel will feature a surfer as a main character). He lives in Laguna Beach, California with his wife and three dogs. To find out more about Chris, visit his Amazon’s author page at http://www.amazon.com/Christopher-Stookey/e/B003UVLDI4/ref=ntt_dp_epwbk_0.

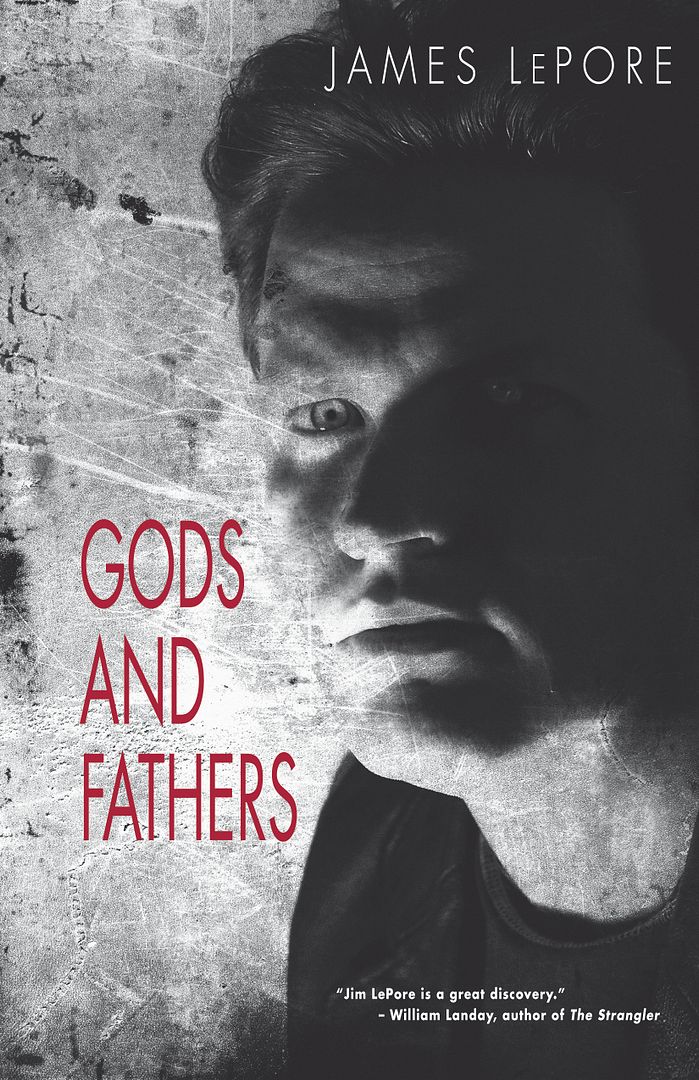

About Terminal Care

Phil Pescoe, the 37-year-old emergency physician at Deaconess Hospital in San Francisco, becomes alarmed by a dramatic increase in the number of deaths on the East Annex (the Alzheimer’s Ward). The deaths coincide with the initiation of a new drug study on the annex where a team of neurologists have been administering “NAF”—an experimental and highly promising treatment for Alzheimer’s disease—to half of the patients on the ward.Mysteriously, the hospital pushes forward with the study even though six patients have died since the start of the trial. Pescoe teams up with Clara Wong—a brilliant internist with a troubled past—to investigate the situation. Their inquiries lead them unwittingly into the cutthroat world of big-business pharmaceuticals, where they are threatened to be swept up and lost before they have the opportunity to discover the truth behind an elaborate cover-up.

With the death count mounting, Pescoe and Wong race against time to save the patients on the ward and to stop the drug manufacturer from unleashing a dangerous new drug on the general populace.

Read the Excerpt!

CHAPTER 1

The death itself wasn’t the unusual thing. The unusual thing was we tried to stop it. That first dying heart came on a Thursday night, a little after midnight on May 5th. I remember the date because it was Cinco de Mayo, a Mexican holiday. There’d been celebrations all day long in San Francisco, including in the Presidio where I was working that night.

I was one of two physicians on duty in the ER at Deaconess Hospital, doing the overnight shift, 6 PM to 6 AM. The early part of the shift had been busy. When I arrived at six o’clock, the waiting room was bursting with patients: drunken revelers with lacerations and sprained ankles, tourists with sunburns, picnickers vomiting from food poisoning, six members of a mariachi band with heat stroke and dehydration. We worked fast, moving from one stretcher to the next, seeing the most critical patients first and moving on.

Then, around ten o’clock, the flow of new patients stopped—abruptly, like water from a faucet turned from on to off. By 11:00 PM, there were only four patients in the waiting room. By 11:45, I finished sewing up my last laceration: a three-inch gash on the forehead of an intoxicated coed from San Francisco State.

Then, there was no one. The emergency department had gone from chaos to serenity.

With nothing to do, Hansen, the other physician on duty, went to catch a nap in the staff lounge. I washed up and went over to join Bill—the night nurse—at the nursing station. We sat with our feet up, drinking black coffee from Styrofoam cups, looking across the empty row of stretcher beds. Bill launched nostalgically into a pornographic tale about a buxom nurse he’d known while serving as a medic during the Gulf War. He’d just reached the climax—so to speak—of his story when, suddenly, the calm of the night was interrupted by an announcement over the intercom:

“Code Blue, East Annex, back station! Code Blue, East Annex, back station! ”

“Christ,” Bill said stopping short in his story. “East Annex? That’s the Alzheimer’s unit.”

“Yeah,” I said. Bill and I exchanged puzzled looks.

“Since when do they call Code Blues on the Alzheimer’s unit?” Bill asked.

The announcement came again, sounding now more urgent. “Code Blue, East Annex! Code Blue!” It was an urgent call for help, hospital jargon for, “Come quick, someone’s trying to die.” And, at that hour of the night, it was the duty of the ER doctor to come and stop the dying. Or at least to try.

I jumped up and grabbed the “Code bag,” the big black duffel bag filled with the equipment we’d need to run the Code: defibrillator unit, intubation tubes, cardiac meds.

“Let’s go,” I said.

“But I was just getting to the good part of my story,” Bill said.

“Save it for later.”

We ran out of the emergency department down the long connector tunnel leading to the East Annex. Why were they calling a Code Blue on the East Annex? I wondered as we ran. In my three years of working at Deaconess, this was the first time I’d been called to a Code on the annex. Normally, they didn’t run Code Blues on the Alzheimer’s ward. The patients there were “DNR”—“Do Not Resuscitate.” In other words, when a patient on the annex stopped breathing or went into cardiac arrest, nothing was to be done. No medical heroics. No breathing machines, no cardiac stimulants, no shocking the heart. This was considered the humane thing to do. All the patients on the annex had at least moderately advanced Alzheimer’s disease; all were near the end of life. To prolong the lives of these poor souls at all costs was not the aim of medical care on the East Annex. The aim of medical care on the East Annex was comfort, a safe environment, and, when the time came, death with dignity.

I heard Bill huffing and puffing, falling behind as we ran down the hall. I turned back and saw him slow to a walk.

“I’ll have to…meet…you…” he said breathlessly.

“Maybe if you give up those damn cigarettes,” I called back as I went around the bend in the tunnel.

“Maybe if…I was…a damn jogger like you,” Bill called out.

At the end of the connector, I came to the door leading to the second floor of the annex. Normally, the door was shut and locked. The East Annex was a locked ward because the patients there—at least the ones who were ambulatory—had a habit of wandering off the ward and getting lost when the doors weren’t locked. Now, as I reached the end of the connector, a rotund, uniformed security guard stood at the door holding it open for me. “Straight ahead, past the back station, on the left,” the guard said.

I went through the door and immediately someone shouted out. “Over here!”

I ran to where six or seven people were gathered outside one of the rooms. There’s always a crowd at any Code Blue. Death, either actual or imminent, is always something that fascinates people. Several of the people in the crowd had no business being there: for example, the ward secretary standing on her tiptoes peering in at the door and the two members of the janitorial staff looking over her shoulder.

Elbowing my way into the room, I got my first look at the patient: an elderly, gray-skinned woman wearing pink pajamas. She lay lifelessly on her back on the bed, the covers tossed back. Four people were gathered closely around the bed working on her. The ward tech, a muscular, crew-cut fellow, was performing chest compressions, pumping away on the old woman’s sternum with the heel of his hand. At the head of the bed stood the respiratory therapist, a skinny African-American fellow named Lamont—I had worked with him in the emergency department. Lamont was holding a mask over the patient’s face and squeezing breaths of oxygen from an oxygen bag. At the foot of the bed stood the Code Blue pharmacist, a young Hispanic woman I’d never seen before; she attentively held her tray of Code Blue medicines, ready to dispense whatever might be called for. The fourth person at the bed was Juanita Obregón, one of the East Annex night nurses. Juanita was also a familiar face. She’d been a good friend of mine since my early days at Deaconess. She stood opposite the ward tech, pressing her fingers into the patient’s groin, feeling for a pulse at the femoral artery.

“Pescoe!” Juanita said as I entered the room. Juanita always called me by my last name—not “Philip” or “Phil” or “Dr. Pescoe,” just “Pescoe”. “Thank God. I was in to see her twenty minutes ago, and she was absolutely fine, watching TV. Then, I came in to turn off the television, and she’s unresponsive. Not breathing, no pulse—out.”

Juanita stepped back as I came over on her side of the bed.

“Who called the Code?” I asked.

“I did,” Juanita said.

“Why? She’s an Alzheimer’s patient, isn’t she?”

“Yes,” Juanita said. “All the patients on the annex are Full Code now, while they’re running the study.”

“Study? What study?”

“Neussbaum and his team. They’re running a drug study, some new experimental treatment for Alzheimer’s.”

I looked at Juanita. I hadn’t heard anything about a drug study on the East Annex. Neussbaum, whom Juanita had referred to, was Tucker Neussbaum, the doctor in charge of the Alzheimer’s unit. He’d never said anything to me about a change in resuscitation status on the unit. Of course, now was not the time to start questioning DNR orders—if the little old lady in the pink pajamas had been declared a Full Code, then so be it. My job was to do everything I could to bring her back to life. Now.

I turned toward the ward tech. “Hold compressions,” I said.

The tech stopped pumping on the patient’s chest and stood back. I pressed my fingers into the old lady’s neck and felt for a pulse. Nothing. I unzipped the Code bag, turned on the defibrillator machine, and took out the defibrillator paddles. Tearing open the woman’s pajama top, I pressed the paddles against her bony chest. The paddles acted like heart monitor electrodes, and we all looked at the TV screen on the defibrillator machine. The neon light showed the woman’s heart tracing, a wiggly pattern running across the screen. The wiggly tracing meant there was still some “life” left in the old woman’s heart, still some electrical activity. The heart rhythm was not normal, however, far from it: the woman’s heart was quivering out of control in a rhythm called “ventricular fibrillation.” In order to save her life, something had to be done to stop the quivering. Otherwise, the woman would die.

“V-fib,” I called out. “I’m going to shock.”

I turned the knobs to charge the defibrillator just as Bill came into the room, wheezing like a steam engine.

“V-fib,” I said. “They’re running some sort of drug study, and all the patients are Full Code.” I pressed the paddles firmly down on the woman’s chest. “Stand clear!” I shouted.

Lamont and the ward tech stepped away from the bed, and I activated the defibrillator. A pulse of electricity shot through the woman’s chest causing her back to arch up. We all looked down at the monitor for the second it takes to re-establish the heart rhythm after the jolt of electricity. The neon tracing appeared on the screen, squiggly and still fibrillating out of control. The shock had failed to convert the old woman’s heartbeat to a normal rhythm.

“Okay,” I said, “epinephrine. We need an IV.”

“She already has one,” Juanita said. “Left forearm.”

I looked at the patient’s left forearm, and, just as Juanita said, there was an IV already in place. A rubber-tipped intravenous catheter had been secured with a gauze wrap and tape. The IV was further held in place by a fishnet stocking covering the entire forearm.

I looked at the pharmacist. “Epinephrine, one milligram,” I said. As the pharmacist reached into her box of medicines, I said to the ward tech, “Continue chest compressions. I’m going to intubate her.”

As in a choreographed dance, everyone went into action. The pharmacist took a syringe of epinephrine—adrenaline—from her tray and handed it to Juanita. Juanita injected the heart stimulant into the IV. The tech resumed his chest compressions, and Lamont resumed bagging oxygen to the patient. Meanwhile, I went to the head of the bed and prepared to put a plastic tube down the old woman’s throat so we could breathe for her more effectively.

They say much of emergency medicine is “cookbook medicine,” and a well-trained monkey can perform much of what emergency physicians do. There’s no better example of this than the Code Blue cardiac arrest. Every step in the Code is based on a precisely defined algorithm, and everyone knows the drill. We’d already performed the first step of the algorithm: shock the patient’s heart with 360 Joules of electricity. This had failed to stop the quivering, so we moved to the next steps of the protocol: a shot of intravenous epinephrine and intubation.

“7.5 tube,” I said.

Bill took the throat tube out of the Code bag and handed it to me. Lamont pulled off the oxygen face mask and stepped aside, and I checked the woman’s mouth to see if there was anything inside that might make it difficult to put the tube down—blood, loose dentures, chunks of food. Her mouth and throat were clear.

“Does this patient have any history of heart problems?” I asked Juanita as I put the laryngoscope blade into the mouth and pried open the jaw.

“No, that’s just it,” Juanita said. “Her only medical history is Alzheimer’s disease. Otherwise, she’s the healthiest patient on the ward. Then again, that’s what I said about the last patient who died. This is the second Code we’ve had in three days.”

“Oh?” I said slipping the throat tube into the trachea.

“Yes. Mrs. Messing, she died on Tuesday.”

Lamont attached the oxygen bag to the end of the tube and began pumping 100% oxygen directly into the woman’s lungs.

“Is Neussbaum here tonight?” I asked.

“No. He just left, half an hour ago,” Juanita said. “His resident is on call tonight, Dr. Chester Mott. He’s here.” Juanita motioned with her head toward a young man standing on the other side of the room.

I looked over at the man. I hadn’t noticed him before; he was slumped down in the shadows of the far corner of the room. He was a short, overweight fellow wearing a black tee shirt and surgical scrub pants; he had carrot orange hair that stood out in all directions. He looked like a resident, all right: young, disheveled, sleep-deprived. I figured he must have been sleeping in the call room when the Code was called.

“Okay, hold compressions,” I said. I looked at the heart monitor: the rhythm was still v-fib. Our efforts were getting us nowhere. “Let’s shock again, 360 Joules.”

Bill charged the machine to 360, and I delivered the shock. Again, no change. What’s more, the amplitude of the heart waves on the screen was getting smaller, flatter. It was a bad sign.

I looked over at the resident. “Want to help, do some chest compressions?” I asked.

The resident looked at me with wide, frightened eyes and shook his head, no. I felt my head cock sideways as I looked at him in surprise. No? That’s odd, I thought. Residents were supposed to be keen to jump in and get involved in a Code Blue. Even if they’re nervous and not really eager to do so, at least they’re supposed to pretend. That’s what they’re there for, to learn. However, I decided to cut Dr. Mott some slack. No doubt he was feeling overwhelmed and anxious, the way most residents feel during the heat of a cardiac arrest. If this had been his rotation through the emergency department, I would have insisted. However, this was the Alzheimer’s ward. The young Dr. Mott was supposed to be learning about dementia and urinary incontinence and bed sores, not fibrillating hearts. No need to press him into service if he didn’t feel comfortable with it.

“Continue compressions,” I said turning back to the tech. I looked at pharmacist. “Amiodarone, 300 milligrams, IV,” I said regurgitating the next step of the protocol.

We continued to work down the algorithm, delivering further shocks and further medications. The room became pungent with the smell of the patient’s singed flesh owing to the repeated shocks. Another bad sign. Between shocks and injections, I watched and supervised the Code team. The ward tech had worked up a heavy sweat pumping away at the chest compressions.

“Need a break?” I asked.

“No, I’m okay.”

“Bill can relieve you. Or,” I said raising my voice a little, “maybe the resident.” Mott didn’t move. He just stood there looking down at the floor, his hands folded diffidently over his protuberant belly.

“No, I’m fine,” the tech said; “I’m good.”

I looked at the patient lying lifelessly on the bed. I wondered what it was that had caused her heart to go suddenly haywire. Heart attack? Juanita had said there was no history of heart problems. I looked at the old woman’s face: she had to be at least eighty-five-years-old. Her hair was white and thinned to near baldness at the crown, her forehead covered with age spots. Her cheeks stood out prominently on the bony face, and her eyes were sunk deep into the sockets. I asked myself again: why in the world were we Coding this bent-up old lady with Alzheimer’s disease?

I asked the tech to hold compressions and looked once again at the heart monitor. The tracing was almost flat now. The woman was going to die. I knew it, everyone knew it—we were just going through the motions now.

“Okay,” I said. I could hear the resigned tone in my own voice. “Let’s try another shock—360 Joules.”

We continued our efforts for another ten minutes until the woman’s heartbeat was truly flat-line on the monitor. I delivered one final, ineffective shock then decided to call it quits.

“I’m going to stop,” I said. “Any objections?”

Not surprisingly, no one objected.

“Okay…,” I said looking up at the clock on the wall. “12:57.”

The tech stopped the chest compressions; Lamont stopped squeezing the oxygen bag; the pharmacist closed her box of medicines. Somewhere in the shadows I saw the young Dr. Mott slip silently out of the room. I looked down at the patient. Her face was now a blue-purple color, and the endotracheal tube stuck out of her mouth like the end of a large fish hook.

“Okay,” Juanita said. “12:57. I’ll mark it down as the time of death.”

The death itself wasn’t the unusual thing. The unusual thing was we tried to stop it. That first dying heart came on a Thursday night, a little after midnight on May 5th. I remember the date because it was Cinco de Mayo, a Mexican holiday. There’d been celebrations all day long in San Francisco, including in the Presidio where I was working that night.

I was one of two physicians on duty in the ER at Deaconess Hospital, doing the overnight shift, 6 PM to 6 AM. The early part of the shift had been busy. When I arrived at six o’clock, the waiting room was bursting with patients: drunken revelers with lacerations and sprained ankles, tourists with sunburns, picnickers vomiting from food poisoning, six members of a mariachi band with heat stroke and dehydration. We worked fast, moving from one stretcher to the next, seeing the most critical patients first and moving on.

Then, around ten o’clock, the flow of new patients stopped—abruptly, like water from a faucet turned from on to off. By 11:00 PM, there were only four patients in the waiting room. By 11:45, I finished sewing up my last laceration: a three-inch gash on the forehead of an intoxicated coed from San Francisco State.

Then, there was no one. The emergency department had gone from chaos to serenity.

With nothing to do, Hansen, the other physician on duty, went to catch a nap in the staff lounge. I washed up and went over to join Bill—the night nurse—at the nursing station. We sat with our feet up, drinking black coffee from Styrofoam cups, looking across the empty row of stretcher beds. Bill launched nostalgically into a pornographic tale about a buxom nurse he’d known while serving as a medic during the Gulf War. He’d just reached the climax—so to speak—of his story when, suddenly, the calm of the night was interrupted by an announcement over the intercom:

“Code Blue, East Annex, back station! Code Blue, East Annex, back station! ”

“Christ,” Bill said stopping short in his story. “East Annex? That’s the Alzheimer’s unit.”

“Yeah,” I said. Bill and I exchanged puzzled looks.

“Since when do they call Code Blues on the Alzheimer’s unit?” Bill asked.

The announcement came again, sounding now more urgent. “Code Blue, East Annex! Code Blue!” It was an urgent call for help, hospital jargon for, “Come quick, someone’s trying to die.” And, at that hour of the night, it was the duty of the ER doctor to come and stop the dying. Or at least to try.

I jumped up and grabbed the “Code bag,” the big black duffel bag filled with the equipment we’d need to run the Code: defibrillator unit, intubation tubes, cardiac meds.

“Let’s go,” I said.

“But I was just getting to the good part of my story,” Bill said.

“Save it for later.”

We ran out of the emergency department down the long connector tunnel leading to the East Annex. Why were they calling a Code Blue on the East Annex? I wondered as we ran. In my three years of working at Deaconess, this was the first time I’d been called to a Code on the annex. Normally, they didn’t run Code Blues on the Alzheimer’s ward. The patients there were “DNR”—“Do Not Resuscitate.” In other words, when a patient on the annex stopped breathing or went into cardiac arrest, nothing was to be done. No medical heroics. No breathing machines, no cardiac stimulants, no shocking the heart. This was considered the humane thing to do. All the patients on the annex had at least moderately advanced Alzheimer’s disease; all were near the end of life. To prolong the lives of these poor souls at all costs was not the aim of medical care on the East Annex. The aim of medical care on the East Annex was comfort, a safe environment, and, when the time came, death with dignity.

I heard Bill huffing and puffing, falling behind as we ran down the hall. I turned back and saw him slow to a walk.

“I’ll have to…meet…you…” he said breathlessly.

“Maybe if you give up those damn cigarettes,” I called back as I went around the bend in the tunnel.

“Maybe if…I was…a damn jogger like you,” Bill called out.

At the end of the connector, I came to the door leading to the second floor of the annex. Normally, the door was shut and locked. The East Annex was a locked ward because the patients there—at least the ones who were ambulatory—had a habit of wandering off the ward and getting lost when the doors weren’t locked. Now, as I reached the end of the connector, a rotund, uniformed security guard stood at the door holding it open for me. “Straight ahead, past the back station, on the left,” the guard said.

I went through the door and immediately someone shouted out. “Over here!”

I ran to where six or seven people were gathered outside one of the rooms. There’s always a crowd at any Code Blue. Death, either actual or imminent, is always something that fascinates people. Several of the people in the crowd had no business being there: for example, the ward secretary standing on her tiptoes peering in at the door and the two members of the janitorial staff looking over her shoulder.

Elbowing my way into the room, I got my first look at the patient: an elderly, gray-skinned woman wearing pink pajamas. She lay lifelessly on her back on the bed, the covers tossed back. Four people were gathered closely around the bed working on her. The ward tech, a muscular, crew-cut fellow, was performing chest compressions, pumping away on the old woman’s sternum with the heel of his hand. At the head of the bed stood the respiratory therapist, a skinny African-American fellow named Lamont—I had worked with him in the emergency department. Lamont was holding a mask over the patient’s face and squeezing breaths of oxygen from an oxygen bag. At the foot of the bed stood the Code Blue pharmacist, a young Hispanic woman I’d never seen before; she attentively held her tray of Code Blue medicines, ready to dispense whatever might be called for. The fourth person at the bed was Juanita Obregón, one of the East Annex night nurses. Juanita was also a familiar face. She’d been a good friend of mine since my early days at Deaconess. She stood opposite the ward tech, pressing her fingers into the patient’s groin, feeling for a pulse at the femoral artery.

“Pescoe!” Juanita said as I entered the room. Juanita always called me by my last name—not “Philip” or “Phil” or “Dr. Pescoe,” just “Pescoe”. “Thank God. I was in to see her twenty minutes ago, and she was absolutely fine, watching TV. Then, I came in to turn off the television, and she’s unresponsive. Not breathing, no pulse—out.”

Juanita stepped back as I came over on her side of the bed.

“Who called the Code?” I asked.

“I did,” Juanita said.

“Why? She’s an Alzheimer’s patient, isn’t she?”

“Yes,” Juanita said. “All the patients on the annex are Full Code now, while they’re running the study.”

“Study? What study?”

“Neussbaum and his team. They’re running a drug study, some new experimental treatment for Alzheimer’s.”

I looked at Juanita. I hadn’t heard anything about a drug study on the East Annex. Neussbaum, whom Juanita had referred to, was Tucker Neussbaum, the doctor in charge of the Alzheimer’s unit. He’d never said anything to me about a change in resuscitation status on the unit. Of course, now was not the time to start questioning DNR orders—if the little old lady in the pink pajamas had been declared a Full Code, then so be it. My job was to do everything I could to bring her back to life. Now.

I turned toward the ward tech. “Hold compressions,” I said.

The tech stopped pumping on the patient’s chest and stood back. I pressed my fingers into the old lady’s neck and felt for a pulse. Nothing. I unzipped the Code bag, turned on the defibrillator machine, and took out the defibrillator paddles. Tearing open the woman’s pajama top, I pressed the paddles against her bony chest. The paddles acted like heart monitor electrodes, and we all looked at the TV screen on the defibrillator machine. The neon light showed the woman’s heart tracing, a wiggly pattern running across the screen. The wiggly tracing meant there was still some “life” left in the old woman’s heart, still some electrical activity. The heart rhythm was not normal, however, far from it: the woman’s heart was quivering out of control in a rhythm called “ventricular fibrillation.” In order to save her life, something had to be done to stop the quivering. Otherwise, the woman would die.

“V-fib,” I called out. “I’m going to shock.”

I turned the knobs to charge the defibrillator just as Bill came into the room, wheezing like a steam engine.

“V-fib,” I said. “They’re running some sort of drug study, and all the patients are Full Code.” I pressed the paddles firmly down on the woman’s chest. “Stand clear!” I shouted.

Lamont and the ward tech stepped away from the bed, and I activated the defibrillator. A pulse of electricity shot through the woman’s chest causing her back to arch up. We all looked down at the monitor for the second it takes to re-establish the heart rhythm after the jolt of electricity. The neon tracing appeared on the screen, squiggly and still fibrillating out of control. The shock had failed to convert the old woman’s heartbeat to a normal rhythm.

“Okay,” I said, “epinephrine. We need an IV.”

“She already has one,” Juanita said. “Left forearm.”

I looked at the patient’s left forearm, and, just as Juanita said, there was an IV already in place. A rubber-tipped intravenous catheter had been secured with a gauze wrap and tape. The IV was further held in place by a fishnet stocking covering the entire forearm.

I looked at the pharmacist. “Epinephrine, one milligram,” I said. As the pharmacist reached into her box of medicines, I said to the ward tech, “Continue chest compressions. I’m going to intubate her.”

As in a choreographed dance, everyone went into action. The pharmacist took a syringe of epinephrine—adrenaline—from her tray and handed it to Juanita. Juanita injected the heart stimulant into the IV. The tech resumed his chest compressions, and Lamont resumed bagging oxygen to the patient. Meanwhile, I went to the head of the bed and prepared to put a plastic tube down the old woman’s throat so we could breathe for her more effectively.

They say much of emergency medicine is “cookbook medicine,” and a well-trained monkey can perform much of what emergency physicians do. There’s no better example of this than the Code Blue cardiac arrest. Every step in the Code is based on a precisely defined algorithm, and everyone knows the drill. We’d already performed the first step of the algorithm: shock the patient’s heart with 360 Joules of electricity. This had failed to stop the quivering, so we moved to the next steps of the protocol: a shot of intravenous epinephrine and intubation.

“7.5 tube,” I said.

Bill took the throat tube out of the Code bag and handed it to me. Lamont pulled off the oxygen face mask and stepped aside, and I checked the woman’s mouth to see if there was anything inside that might make it difficult to put the tube down—blood, loose dentures, chunks of food. Her mouth and throat were clear.

“Does this patient have any history of heart problems?” I asked Juanita as I put the laryngoscope blade into the mouth and pried open the jaw.

“No, that’s just it,” Juanita said. “Her only medical history is Alzheimer’s disease. Otherwise, she’s the healthiest patient on the ward. Then again, that’s what I said about the last patient who died. This is the second Code we’ve had in three days.”

“Oh?” I said slipping the throat tube into the trachea.

“Yes. Mrs. Messing, she died on Tuesday.”

Lamont attached the oxygen bag to the end of the tube and began pumping 100% oxygen directly into the woman’s lungs.

“Is Neussbaum here tonight?” I asked.

“No. He just left, half an hour ago,” Juanita said. “His resident is on call tonight, Dr. Chester Mott. He’s here.” Juanita motioned with her head toward a young man standing on the other side of the room.

I looked over at the man. I hadn’t noticed him before; he was slumped down in the shadows of the far corner of the room. He was a short, overweight fellow wearing a black tee shirt and surgical scrub pants; he had carrot orange hair that stood out in all directions. He looked like a resident, all right: young, disheveled, sleep-deprived. I figured he must have been sleeping in the call room when the Code was called.

“Okay, hold compressions,” I said. I looked at the heart monitor: the rhythm was still v-fib. Our efforts were getting us nowhere. “Let’s shock again, 360 Joules.”

Bill charged the machine to 360, and I delivered the shock. Again, no change. What’s more, the amplitude of the heart waves on the screen was getting smaller, flatter. It was a bad sign.

I looked over at the resident. “Want to help, do some chest compressions?” I asked.

The resident looked at me with wide, frightened eyes and shook his head, no. I felt my head cock sideways as I looked at him in surprise. No? That’s odd, I thought. Residents were supposed to be keen to jump in and get involved in a Code Blue. Even if they’re nervous and not really eager to do so, at least they’re supposed to pretend. That’s what they’re there for, to learn. However, I decided to cut Dr. Mott some slack. No doubt he was feeling overwhelmed and anxious, the way most residents feel during the heat of a cardiac arrest. If this had been his rotation through the emergency department, I would have insisted. However, this was the Alzheimer’s ward. The young Dr. Mott was supposed to be learning about dementia and urinary incontinence and bed sores, not fibrillating hearts. No need to press him into service if he didn’t feel comfortable with it.

“Continue compressions,” I said turning back to the tech. I looked at pharmacist. “Amiodarone, 300 milligrams, IV,” I said regurgitating the next step of the protocol.

We continued to work down the algorithm, delivering further shocks and further medications. The room became pungent with the smell of the patient’s singed flesh owing to the repeated shocks. Another bad sign. Between shocks and injections, I watched and supervised the Code team. The ward tech had worked up a heavy sweat pumping away at the chest compressions.

“Need a break?” I asked.

“No, I’m okay.”

“Bill can relieve you. Or,” I said raising my voice a little, “maybe the resident.” Mott didn’t move. He just stood there looking down at the floor, his hands folded diffidently over his protuberant belly.

“No, I’m fine,” the tech said; “I’m good.”

I looked at the patient lying lifelessly on the bed. I wondered what it was that had caused her heart to go suddenly haywire. Heart attack? Juanita had said there was no history of heart problems. I looked at the old woman’s face: she had to be at least eighty-five-years-old. Her hair was white and thinned to near baldness at the crown, her forehead covered with age spots. Her cheeks stood out prominently on the bony face, and her eyes were sunk deep into the sockets. I asked myself again: why in the world were we Coding this bent-up old lady with Alzheimer’s disease?

I asked the tech to hold compressions and looked once again at the heart monitor. The tracing was almost flat now. The woman was going to die. I knew it, everyone knew it—we were just going through the motions now.

“Okay,” I said. I could hear the resigned tone in my own voice. “Let’s try another shock—360 Joules.”

We continued our efforts for another ten minutes until the woman’s heartbeat was truly flat-line on the monitor. I delivered one final, ineffective shock then decided to call it quits.

“I’m going to stop,” I said. “Any objections?”

Not surprisingly, no one objected.

“Okay…,” I said looking up at the clock on the wall. “12:57.”

The tech stopped the chest compressions; Lamont stopped squeezing the oxygen bag; the pharmacist closed her box of medicines. Somewhere in the shadows I saw the young Dr. Mott slip silently out of the room. I looked down at the patient. Her face was now a blue-purple color, and the endotracheal tube stuck out of her mouth like the end of a large fish hook.

“Okay,” Juanita said. “12:57. I’ll mark it down as the time of death.”

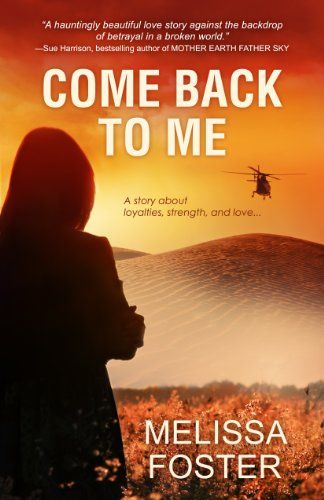

My review will be posted at a later date.

1 comments:

Now this is a different type of read but one I'm willing to examine since I know you would not steer me the wrong way.. after my needle story.. So guide me and Doc I'm a Coming your way.

Post a Comment